Contact Lorca Tourist Office on +34 968 441 914

or to send an Email

Click Here

Contact Lorca Tourist Office on +34 968 441 914

or to send an Email

Click Here

To contact Lorca Tourist office please use the secure enquiry form provided below.

Lorca as we know it today is the third largest city in the Region of Murcia, with a population in the municipality of over 90,000 and a deserved reputation for having one of the richest histories and cultures in south-eastern Spain.

But the chain of developments and events which led to Lorca becoming what is is in modern times is one which begins a very long time ago indeed: in fact some might argue that the present-day prominence of the city owes much to the geological processes which endowed it with such an advantageous location at the foot of the mountains which stand to the north and looking out over the fertile plain of the River Guadalentín.

Remains from the Lower Paleolithic

The huge municipality of Lorca – its area of 1,675 square kilometres makes it the second largest in Spain, roughly on a par with the English counties of Surrey and Worcestershire – has been home to human habitation since over a million years ago, a fact which is most probably due to two factors.

Firstly, evidence has been found in recent years which suggests that Man (and his predecessors) may not in fact have entered Europe from Africa via the Middle East, but across the Straits of Gibraltar, and if this is the case then it is logical that areas close to the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula would have been among the first in which the predecessors of modern man settled.

Secondly, there is no doubting the suitability of parts of modern-day Lorca for early humans and their predecessors, with a wide variety of landscapes ranging from the coast and the fertile Guadalentín plain in the south to the mountains and higher ground in the north. In fact, it is in the foothills of the Sierra del Caño to the north-west of the city, and in the plains of Coy, Avilés and Doña Inés that the scattered remains of the oldest settlements have so far been found, although there are others in the valleys of the rivers Comeros, Luchena, Turrilla and Guadalentín, and the coastline is also sprinkled with sites which bear witness to the presence of human beings in Lorca since the Paleolithic.

The plain of El Castillo in the Sierra del Caño is one of the most interesting archaeological deposits in the Region of Murcia, with the oldest remains discovered here dating from the long period of the Lower Paleolithic or Old Stone Age (1,500,000 to 95,000 years BC). Among the findings are flint tools and hand-axes belonging to the Acheulean culture, which it is thought must have been fashioned by homo erectus living in an open-air settlement on the terraces of the River Turrilla.

Neanderthals in Lorca

During the Middle Paleolithic, though, the caves and natural shelters of the mountains of Lorca were principally inhabited by Neanderthals, who made tools which indicate an economy based on a hunter-gatherer existence, and which were more efficient and specialized than those of Acheulean cultures. Homo neanderthalensis is known to have inhabited various sites in the municipality of Lorca, including Cueva Perneras (Ramonete), Barranco de la Hoz (Zarazdilla de Totana) and the Cerro Negro del Jofré (Zarcilla de Ramos).

The Neanderthals lived not in permanent settlements, but in different locations at different times of year, according to factors such as physical comfort and the availability of food. Thus, they alternated between open-air settlements on the banks of the rivers Alcaide, Luchena, Turrilla, Corneros and Guadalentín, and open caves in the limestone outcrops of the hills. In this way they were close all year round to the resources which were most important for their communities: food, seams of flint for their tools, and reliable water supplies.

Techniques of stonework employed by the Neanderthals are very distinctive, and Neanderthal sites show a manipulation of flint that has resulted in the classification of the period between 95,000 BC and 35,000 BC as the “Mousterian culture” of the Middle Paleolithic.

The name is simply taken from the “Le Moustier” site in the Dordogne region of France where the technique used to make flint tools using a flint knapping technique which has become known as the Levallois technique (due to the discovery of tools in the Levallois-Perret suburb of Paris,) was definitively associated and identified. Since the first discoveries of the technique used were classified, it has become clear that the techniques were also copied by early Homo sapiens, who supplanted Neanderthals and went on to evolve into modern man.

The Cerro Negro del Jofré fulfils all of the criteria of a typical Mousterian Neanderthal habitat. Firstly, it is situated at the foot of a rock wall, and its orientation means that it receives sunlight during the day. At the same time, it is close to a freshwater spring. In addition, from the higher parts of the Cerro Negro the inhabitants could look out over the whole area, to see if anyone was approaching from any direction. In the valley of the River Turrilla they could catch fish, and the nearby mountains of the Sierra de la Culebrina provided a good hunting ground.

In short, this is just the kind of site the Neanderthals lived and thrived in before they were superseded by Homo sapiens, and the skeletal remains found in the Cueva de Perneras show that the groups who lived there successfully hunted rabbit and deer. There is also evidence that they fished, and even brought seafood from the coast (which at that time was 3.5 km nearer than today!)

Neanderthals became extinct as a separate definable species from Homo sapiens around 40,000 years ago. Of course, the debates continue as to how much interaction took place between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and whether Homo sapiens were ultimately responsible for the demise of the Neanderthals, in spite of the fact that there is clear evidence of interbreeding between the two distinct species.

Examples of prehistoric remains from Lorca can be found in Sala 1 of the Municipal Archaeological Museum

The Late Stone Age

As Homo Sapiens developed and gradually replaced the Neanderthals they found means to improve their technological proficiency, producing smaller and better-fashioned items than those of the previous period, and some of these have been found at the archaeological sites of Los Calares, Barranco de la Hoz and the Cueva de Perneras.

More importantly, though, they also established themselves in permanent year-round settlements, and farmed the land in one place rather than moving with the seasons to different locations: in short, these early humans tailored the environment to their needs, rather than being dictated to by nature.

This meant the first emergence of the production economy which was to become one of the main characteristics of the late Neolithic, or Late Stone Age and traces of the period have been found within the municipality of Lorca at a range of sites such as El Enebro, Fuente Gil, Peña María, Barranco de la Hoz, Los Calares, El Peralejo and Peñas de Béjar.

However, they really are only traces, such as the remains of polished stone, and it appears that there were few if any large settlements in Lorca during this period of pre-history. It may be that the hunter-gatherer way of life was so successful here that it persisted, or indeed it may be that the last phase of the Neolithic lies buried under later settlements, or under the heavy lime deposits of the Guadalentín valley, but the first signs of Late Stone Age settlements in the municipality go back only as far as the very end of the Neolithic, shortly before 2000 BC.

Nonetheless, some prehistoric cave paintings have been found at a dozen or so sites in the municipality, the earliest dating from the Neolithic and the most notable being in the caves of El Mojao and Los Gavilanes. The former includes images belonging to both the Levantine and Schematic types of rock art, while the latter features only Schematic designs.

The Bronze Age and the Cueva Sagrada

The calcolithic culture of the Bronze Age developed in the third millennium BC, surviving in the south-east of the Iberian peninsula until the arrival of the Argaric culture. These people chose to live in places which had ample natural resources and were near to fresh water, and in the municipality of Lorca this is reflected in the area around the River Guadalentín, especially in the zones known as El Capitán and Cueva Sagrada.

The site at El Capitán, near the outlying village of Zarcilla de Ramos, is one of the most important circular settlements of prehistoric huts in the municipality of Lorca. It includes a flint workshop where craftsmen, expert in working hard stone, made arrowheads and knives, items which are typical of the material culture of the era, as are the large containers with symbolic decorations and the cross-shaped idols made out of bone.

The funeral traditions of these settlers consisted of mass graves in burial grounds which were set away from the settlements themselves, a good example of which can be seen at Cueva Sagrada, in the foothills of the Sierra de la Tercia. Human remains with signs of partial cremation have been found here, accompanied by grave goods.

The remains have also been found of the oldest surviving linen tunic in Europe, estimated to be over 4,200 years old, and the eneolithic settlement at Murviedro, just one kilometre south of the hill on which Lorca castle now stands, had its own burial ground almost next door.

This linen can still be seen today in the Municipal Archaeological Museum in Lorca and is an astonishingly rare find, extraordinary conditions allowing it to survive until modern times. Located in the basement of the museum it is exhibited alongside a reproduction loom showing how it would have been created.

The Argaric and Iberian cultures in Lorca

Between approximately 2200 and 1550 BC the Argaric Culture was dominant in south-eastern Spain, building and occupying multiple settlements, most of them on hilltops, in the Region of Murcia and the provinces of Almería, Granada, Alicante and Jaén. This period falls within what is broadly termed the Bronze Age, a stage in technological development which coincides with a revolution in social and urban organization, territorial definition, the emergence of funeral rites and the expansion of the human population.

Internally the Argaric world appears to have been divided into territorial definitions and to have been based on a hierarchical structure, excavations demonstrating clear definitions between those who controlled and those who were controlled, as well as a clear indication of conformity and control in the artefacts recovered. Recent excavations at the La Bastida site in Totana indicate a slave or socially deprived class, with a 10% upper class, 50% warrior and craftsman class and a 40% slave class, this distribution of population clearly visible in the manner of interment.

This definition of class is most clearly seen in the distribution and control of metals, the majority of the metallic grave goods belonging to the upper population level. The ownership of metal enabled those bearing weapons to control those without them, and weaponry is only found in the male grave goods of those who clearly had social status.

There is no similarity between the Argaric settlements and other inhabitants of the same area, indicating the Argarics to be a distinct population and the standardisation of artefacts across their communities indicates a rigid level of control and conformity, for example ceramics across all population settlements are virtually identical in their form and follow a standard volume, indicating control of measurement.

The distribution of artefacts indicates clear specialisation and a system of interchange, as some vital elements such as grinding stones for grinding flour and metal ingots for casting tools and weapons have a clear geographical origin. There is also evidence that smaller, outlying settlements would have depended on the larger settlements for the gathering, supply and distribution of goods. The larger centres, however, appear to have drawn in a workforce for specific activity, ie grinding flour and undertaking manual production work, the labouring class who did not necessarily live within the settlement environment.

Only now is evidence being uncovered of Argaric remains in Lorca, and some experts have even theorized that the hill on which the castle stands could have been at the origin of Argaric culture and was formerly a substantial settlement.

However, there are various other sites of importance, mainly between Coy and the city of Lorca, among them the one at Los Cipreses, which has provided insights into the Argarics’ beliefs regarding an afterlife. The site has been converted into an archaeological park showing remains of the structures and the burials they contained.

On the Cerro de Las Viñas hill two kilometres south of Coy there is another important Argaric site, located at an altitude of 913 metres above sea level and occupying the brow and the southern slope of the hill. Those who lived in the homes whose remains have been uncovered are known to have engaged in agriculture on the surrounding plain, and they also hunted deer and rabbits as well as gathering fruit. The water supply was from the River Turrilla.

In addition, the settlement at Cerro de las Viñas was protected by defensive walls, one interior, perhaps surrounding a kind of fortress, and the other more extensive and taking in the whole of the population. The burial site on the hill includes one domestic dwelling and numerous grave goods have also been unearthed.

Argaric artefacts can be seen in Salas 3 and 4 of the Municipal Archaeological Museum.

Iberians

The dominance of the Argaric culture was followed by the emergence of the Iberians in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, with their principal activity from the 5th to the 1st century BC, and again these groups were attracted by the strategic advantages of the hill on which Lorca castle now stands. It was here and on the south-western slopes of the Sierra del Caño that they built their towns in a territory which was limited to the south by the River Guadalentín.

Technologically this civilization belongs to the Iron Age in what is generally referred to as the Second Iron Age, i.e. from 600 BC approximately until the birth of Christ and genetically they are not traceable as an isolated population, so the term Iberians refers to the indigenous peoples who inhabited the Mediterranean coastline between Upper Andalucía and the River Hérault, in the South of France, from the 8th to the 1st century BC. This encompassed modern day Andalucía, Albacete, Murcia, Valencia, Catalunya and some parts of Aragón.

It was the Greeks who gave the name of “Iberians” to the inhabitants of the peninsula, which in turn was known as Iberia. At the time these people spoke Iberian, the written version of which consists of syllabic and alphabetical symbols and has been found at the archaeological sites of El Cigarralejo (Mula) and La Serreta (Cieza).

From the settlement on the castle hill the Iberians looked out over the communications route between the eastern and southern coasts of the Peninsula as well as the trail which led inland towards the centre of what is now Spain, and at the same time the hill was an impregnable defensive location. An acropolis stood on the summit, perhaps an indication of the influences brought by trading with the Eastern Mediterranean peoples, including the Phoenicians, whose main interest lay in the silver and other minerals which were mined from the mountains along the coast.

Excavation of the Iberian remains within Lorca centre are complicated by the fact that subsequent inhabitants built over the same sites, although remains do come to light during building works.

The finest example of Iberian art yet found in Lorca is the white limestone sculpture of a lion which came to light at the necropolis of La Fuentecica del Tío Garrulo in Coy. The lion is sitting with its front paws in front of him, and the stonework dating from the 4th or 5th century BC clearly shows the lines of the animal’s ribcage marked on the stone.

The finest example of Iberian art yet found in Lorca is the white limestone sculpture of a lion which came to light at the necropolis of La Fuentecica del Tío Garrulo in Coy. The lion is sitting with its front paws in front of him, and the stonework dating from the 4th or 5th century BC clearly shows the lines of the animal’s ribcage marked on the stone.

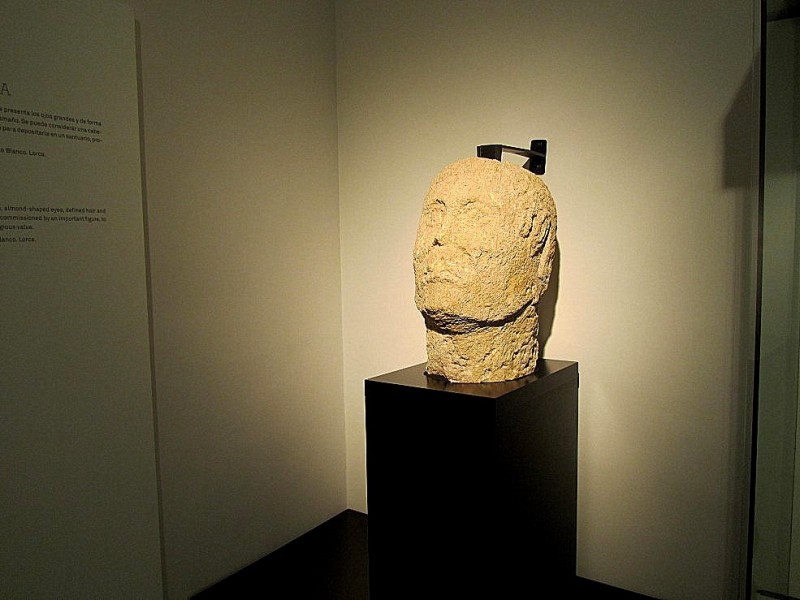

Salas 5 and 6 of the Municipal Archaeological Museum are dedicated to the Iberians, showing some of the many trade goods found in their burials, along with their personal possessions. These vary considerably depending on the social status of the individual enterred, and in Lorca some exceptional pieces have been found attesting to the wealth of these former inhabitants, amomngst them an impressive ceramic "Kernos", a stone head found in calle Carríl and two stone relieves with equestrian motifs which came from la Hoya de la Escarihuela in Lorca.

The Iberians traded for trade goods from all of the colonists, exchanging them for raw materials, and among the items found on archaeological sites, mainly in burials, the most important group is luxury crockery, mainly from Greece, especially the city of Athens, during the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Later in the history of Iberian culture, these luxury or semi-luxury items were bought from Italy or the Greek colonies in the north-east of the peninsula (Ampurias and Rosas).Jewellery also frequently reflects the social status of the deceased, while domestic and agricultural implements show the influence of external trade contact.

It was never in their character to unite and form a single Iberian state; indeed the individual tribes were often engaged in power conflicts and territorial disputes, although they are generally classified as being one group of people by strong resemblances in their habits, religion, trade and languages.

The Iberians were gradually absorbed into the culture of the Romans following their invasion and had disappeared as a definable culture by the middle of the 1st century BC, becoming "Romanised" by the invaders.

The next stage in the history of Lorca is covered by Part 2, which traces the story from the arrival of the Romans in the last centuries BC to the occupation by the Moors.

Part 3 focuses on the "Modern era" in Lorca, from the Reconquist to the present

Click here to see more articles about the history of Lorca as well as a full cultural agenda and further information about the city: LORCA TODAY

Hello, and thank you for choosing CamposolToday.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Camposol Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Camposol Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@camposoltoday.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb